I’ve been absent from this blog for nearly a year, during which I underwent some surgery and then moved out of the 3rd-floor walk-up where I’d lived for 37 years to a garden apartment in another part of Brooklyn. I’m finally recovered and settled, more or less, and ready to write again. It’s good to be back!

It seems fitting that I resume my blog with a tribute to a dear friend who died this summer, but who will live in my heart forever. His name was Norman Walsh Taylor. I knew him only as Taylor. (I’ll tell you why in a minute.)

It seems fitting that I resume my blog with a tribute to a dear friend who died this summer, but who will live in my heart forever. His name was Norman Walsh Taylor. I knew him only as Taylor. (I’ll tell you why in a minute.)

In my imagination Taylor could have been a storybook character, like one who lives deep in the woods conjuring magic, talking with the animals, dancing in the moonlight, showing up in the village disguised as a streetlamp or a cat or Jesus, the holy stranger who suddenly appears to bless the good-hearted and console those who mourn.

People on the fringe of society were drawn to him — poets and dreamers and those trapped in nightmares. Was it the tilt of his head? the lilt in his step? sparkling eyes? contagious laugh? the way he said “Hello Luv!”

GANDHI, KAI, TAYLOR, AND ME

Taylor and I first met in Philadelphia in the early 1980s at a nonviolence workshop run by Movement for a New Society (MNS). We sat cross-legged on the floor, and, when we introduced ourselves around the circle, something clicked. From that moment, time and space held little significance in our friendship except for the occasional lament, “Oh, I wish you lived just around the corner so we could talk over tea.”

Taylor was a genuine free spirit, bon vivant with a heart aching for the whole hurting world, courageous activist, determined to do whatever he could to make a difference on our fragile planet. He was, from day one, supportive of my writing and passions, ready with a listening ear and words of encouragement.

Taylor had not always been Taylor. Approaching middle age, he had decided to drop his birth name — Norman Walsh — and adopt a mononym. In a consciously bold, feminist, anti-patriarchal move, he’d chosen to be known by his mother’s maiden name: Taylor. Later, he would reclaim the name Norman, but he was always Taylor to me.

Gandhi visiting Lancashire, UK in 1931

Not only had his mother been a seamstress (tailor), but his parents had been textile workers in Lancashire, UK, in 1931 when Gandhi visited, mid-boycott of English cotton goods, (part of his Indian self-sufficiency movement) and pleaded for worker solidarity. Even those who’d already lost their jobs in England greeted Gandhi as an anti-imperialist hero, including Taylor’s parents, who packed up and moved to Canada in search of new work.

When we met, Taylor was suffering deep emotional turmoil. His beloved friend Kai Yutah Clouds, a literacy activist working in Guatemala at the invitation of the Mayas, had been kidnapped at gunpoint by security officers in October, 1980, in front of 100 witnesses. His body was found the next day many miles away in Antigua. Kai, who’d been researching the genocide of Native peoples in Central America, had been tortured to death by Guatemalan government forces as a warning to other activists. In memory of Kai, Taylor created a slide bank to empower grassroots social change groups to make their own slide shows and documentaries on everything from consumerism to animal rights, pollution to racism, peace activism to Native Peoples’ struggles, patriarchy to mercury poisoning.

Over the years, the crazy quilt of Taylor’s unconventional, counter-cultural life was slowly revealed to me — including his childhood vaudeville act in Canada. He had been billed as the “youngest ventriloquist in the British Empire” and a Gracie Fields impersonator. He had done his doctoral work at Yale and, writing as Norman Walsh, had won a prestigious Canadian Playwriting Contest. I have the first edition, illustrated hardcover copy inscribed to me, and an anthology, The Best Short Plays: 1955-56, which includes his award-winning work beside plays of Tennessee Williams and Archibald MacLeish.

Over the years, the crazy quilt of Taylor’s unconventional, counter-cultural life was slowly revealed to me — including his childhood vaudeville act in Canada. He had been billed as the “youngest ventriloquist in the British Empire” and a Gracie Fields impersonator. He had done his doctoral work at Yale and, writing as Norman Walsh, had won a prestigious Canadian Playwriting Contest. I have the first edition, illustrated hardcover copy inscribed to me, and an anthology, The Best Short Plays: 1955-56, which includes his award-winning work beside plays of Tennessee Williams and Archibald MacLeish.

LISTENER-ACTIVIST EXTRAORDINAIRE

As impressive and far-out as his accomplishments were, I already knew they were not the important things to Taylor. What mattered was his engagement with this harsh and hurtful world as a deep listener, gentle soul, often terrified but determined nonviolent activist fighting against the oppression of sentient creatures, human and other.

During the Civil Rights Movement, he went to Mississippi. Once, he was asked by fellow activists to calm a tense standoff with the Ku Klux Klan. He was successful that day, but the experience scared and scarred him.

He became a skilled nonviolence trainer, deeply involved in Movement for a New Society, and led Group Process workshops across Canada. He served for a time as the National Coordinator for the Canadian Friends (Quakers) Service Committee.

Gays and Lesbians Aging, Toronto

Taylor fought for LGBTQ rights and was a lover of men. In an elegant coffee table book published by the City of Toronto and often presented to visiting dignitaries, there’s a color photo of Taylor, laughing in front of a banner proclaiming “Gays and Lesbians Aging.” One of the greatest blessings of his life was to fall in love with Leo. They got married in the summer of 2014.

A skilled deep-listener, Taylor was a magnet for remarkable adventures. Once, by invitation, he walked gingerly across a frozen lake to reach a designated meeting ground to help two divisions within a First People’s tribe break a century’s old impasse. He earned their deep thanks, but, on the trek home, as the ice began to crack under his feet, Taylor, shivering with cold and terror, had a heart attack. Another time, he was chosen by a Native Canadian tribal council to help resolve a dispute between them and the Canadian government.

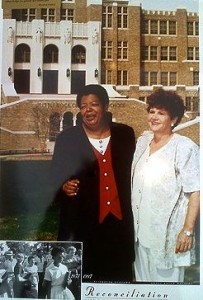

Taylor, Dee, and me

Always, at his apartment or mine, there were cats to cuddle and cherish, and dogs, like Dee. Aging went hard on this beloved canine who had a fierce hold on life. As the dog lost sight, hearing, and mobility, Taylor pulled him through the streets of Toronto in a little red wagon.

A devoted animal rights activist, he volunteered at Fauna Foundation, Canada’s only chimpanzee sanctuary, for 14 years to his last days and served on their Board of Directors. He was beloved of the chimps. Many of them had survived years of torture in biomedical research or neglect after outliving their usefulness in the entertainment industry. Taylor knew their names, their fears, and what calmed them. He listened, and they communicated with him.

Taylor felt a special connection with Pepper, a chimp severely traumatized by 27 years of the most horrendous medical experiments. Pepper touched many lives after she came to the sanctuary and learned to trust a few humans, Taylor being one. He emailed me in July 2012:

Last week I dashed to Montreal to say goodbye to my chimp friend Pepper who was in kidney failure. But when she saw me, and even though she was in enormous distress, she thrust her hand toward me and stroked my palm a half dozen times before collapsing again.

Taylor devoted several years to researching inter-species relationships — cats and crows, kittens and apes, deer and dogs.

OUR DANCE OF LIFE AND DEATH

Taylor was magical, remarkable, quirky, campy, kind. I reach into a grab bag to pull out a list of partial identities to hint at the whole. He was scholar prince, holy fool, and fairy godmother, crusader, confidante, Quaker, author of travel books, Broadway show tune belter-outer (with me as his delighted accompanist) …

Taylor was magical, remarkable, quirky, campy, kind. I reach into a grab bag to pull out a list of partial identities to hint at the whole. He was scholar prince, holy fool, and fairy godmother, crusader, confidante, Quaker, author of travel books, Broadway show tune belter-outer (with me as his delighted accompanist) …

I loved visiting Taylor. The first time, I stayed in a rustic cabin behind his upstate New York home in Oneonta near the college where he was a professor, teaching drama and literature. He called it Blake House for his favorite poet (oh “Tyger, tyger burning bright”).

Later, when he moved back to Toronto, my favorite apartment was the one he called his Tree House. A branch of a city tree had grown through his open window and stretched over his bed! It was fabulous.

It seems right that Halloween became central to our early friendship, with its dance of life and death. Is this what drew us together — our shared awareness of temporality and the willingness to risk engaging in the drama of it all?

Pack of cards shuffling at NYC’s Village Halloween Parade

We established a decade-long tradition of celebrating Halloween together in Greenwich Village, joining other revelers who wove through the tight streets. In those early years, the parade passed the Jefferson Market Library, where a huge, hairy spider climbed up and down the tower.

The marchers we most enjoyed were those who came as a coordinated creative act:

~ the pack of cards which ran amok when one card called out the command, “Shuffle!!”

~ the bull and bear who talked into toy phones, frantically shouting “Buy!” “Sell!”

~ the giant puppet heads and impressive stilt walkers from Vermont’s Bread and Puppet Theatre

~ the mustachioed “Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence” who wore nuns’ habits and Groucho glasses. They’d glide by silently with hands folded, arranged in descending order from tallest to shortest.

TIME TO GO

The last time I saw Taylor, he was in a hospital in Toronto. It was serious, but he would live more than another year. We both knew it was unlikely we’d see each other again.

The last time I saw Taylor, he was in a hospital in Toronto. It was serious, but he would live more than another year. We both knew it was unlikely we’d see each other again.

When it was time to part, he propped his red-slippered feet on his walker, waved “like the Queen of England,” and sang, “Wish me luck as you wave me goodbye, Cheerio, here I go on my way,” a WWII song sung by Gracie Fields in the movie Shipyard Sally.

Over the past year, Taylor said goodbye to me in various ways, as though he were slowly fading from the world, waving goodbye through his emails and letters. He died peacefully at home, with Leo by his side, on Sunday, August 7, 2016. The landscape of my life has changed with his passing.

In my mind’s eye, I can see Taylor. He’s giving me the royal wave, like the queen would do, straight-faced, but with a sparkle in his eye. How blessed I’ve been by his example and his friendship and all that laughter and all those tears.

Oh, Taylor, it went by so fast. Cheerio, my remarkable friend. I’m so grateful for all the serendipity.

TO GO DEEPER

Obituary: Norman Walsh Taylor

Fauna Foundation website for Canada’s only Chimpanzee Sanctuary: Taylor asked that donations in his memory be made to this foundation (Fauna Foundation, 3802 Chemin Bellerive, Carignan, Quebec J3L-3P9)

Book: Oppose and Propose: Lessons from Movement for a New Society by Andrew Cornell, AK Press, 2011.

History of NYC’s Village Halloween Parade

Gandhi’s Visit to England (Lancashire, 1931)

Videos

The Chimps of Fauna Sanctuary

Gracie Fields singing “Wish Me Luck As you Wave Me

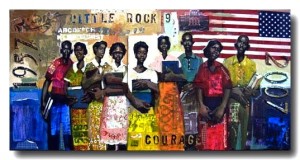

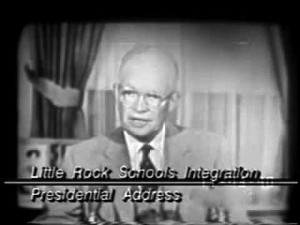

After several attempts, Elizabeth decided to head back to the bus stop. Even then, the racists followed her, cursing and spitting. Boys made loud plans to get a rope, wrap it around her neck, and hang her.

After several attempts, Elizabeth decided to head back to the bus stop. Even then, the racists followed her, cursing and spitting. Boys made loud plans to get a rope, wrap it around her neck, and hang her.

In 1992, Central High School was declared a National Historic Landmark. A Visitors Center was later added nearby, on Daisy Bates Drive.

In 1992, Central High School was declared a National Historic Landmark. A Visitors Center was later added nearby, on Daisy Bates Drive.

A Mighty Long Way: My Journey to Justice at Little Rock Central High School

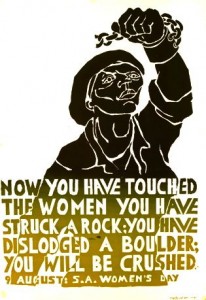

A Mighty Long Way: My Journey to Justice at Little Rock Central High School In Pretoria, on August 9, 1956, 20,000 women stood for a full thirty minutes in silence. It is said that even the babies on their mothers’ backs did not cry.

In Pretoria, on August 9, 1956, 20,000 women stood for a full thirty minutes in silence. It is said that even the babies on their mothers’ backs did not cry. The women had come from across South Africa to see the prime minister, deliver a petition, and protest, once again, the extension of the pass laws to women.

The women had come from across South Africa to see the prime minister, deliver a petition, and protest, once again, the extension of the pass laws to women. Their mothers had resisted pass laws in 1913, and they were bound by honor to bestow the legacy of resistance upon their daughters and granddaughters.

Their mothers had resisted pass laws in 1913, and they were bound by honor to bestow the legacy of resistance upon their daughters and granddaughters. Because the apartheid regime had officially banned all processions in Pretoria for the day, the women arranged themselves in careful groupings of two or three and walked slowly up the wide avenue to an amphitheater which was ringed with gardens and government buildings.

Because the apartheid regime had officially banned all processions in Pretoria for the day, the women arranged themselves in careful groupings of two or three and walked slowly up the wide avenue to an amphitheater which was ringed with gardens and government buildings. The women’s silence took on a life of its own — pulsing between them, solid beneath their feet, alive in their breathing together, raging through their veins.

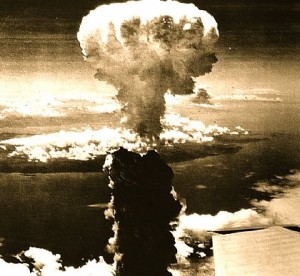

The women’s silence took on a life of its own — pulsing between them, solid beneath their feet, alive in their breathing together, raging through their veins. On the clear, sunny morning of August 6, 1945, a United States airplane, the Enola Gay, suddenly appeared in the sky over Japan and dropped a bomb on the city of Hiroshima.

On the clear, sunny morning of August 6, 1945, a United States airplane, the Enola Gay, suddenly appeared in the sky over Japan and dropped a bomb on the city of Hiroshima.

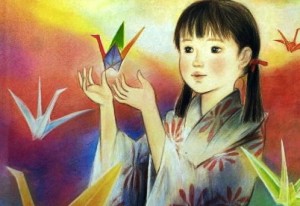

Sadako was too little to remember being carried to the river, or how her grandmother went back to the house to get something and was never seen again.

Sadako was too little to remember being carried to the river, or how her grandmother went back to the house to get something and was never seen again.

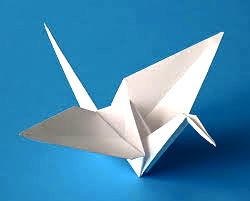

One day, Sadako was given a square piece of golden paper and taught to fold it into a crane. She was reminded that, according to an ancient Japanese legend, the crane is the bird of happiness and youth. It is said, that anyone who folds 1,000 paper cranes would be granted a wish.

One day, Sadako was given a square piece of golden paper and taught to fold it into a crane. She was reminded that, according to an ancient Japanese legend, the crane is the bird of happiness and youth. It is said, that anyone who folds 1,000 paper cranes would be granted a wish. Sadako’s medicine came wrapped in red paper squares. She saved these and turned them into magic cranes. Other patients in the hospital heard about Sadako’s cranes and came by the room to see the girl and her magic birds.

Sadako’s medicine came wrapped in red paper squares. She saved these and turned them into magic cranes. Other patients in the hospital heard about Sadako’s cranes and came by the room to see the girl and her magic birds. CHILDREN LEAD THE WAY

CHILDREN LEAD THE WAY

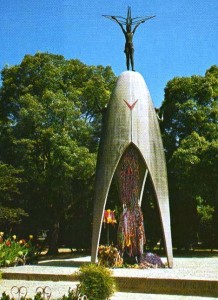

News of the statue spread, and children everywhere began folding paper cranes and sending them to the Children’s Peace Monument — children in the United States, Russia, Brazil, India, Iran, Spain, Sweden, France; children in Poland, South Africa, Israel, Thailand, Australia. Still, every year, children send thousands of paper cranes to be placed in glass cases near the monument — each crane is a prayer for peace.

News of the statue spread, and children everywhere began folding paper cranes and sending them to the Children’s Peace Monument — children in the United States, Russia, Brazil, India, Iran, Spain, Sweden, France; children in Poland, South Africa, Israel, Thailand, Australia. Still, every year, children send thousands of paper cranes to be placed in glass cases near the monument — each crane is a prayer for peace. Mary Harris Jones lost everything. Everything!

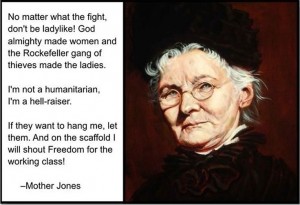

Mary Harris Jones lost everything. Everything! No one thought seventy-five thousand workers in Pennsylvania would go on strike, but they did. At least 10,000 of those strikers were children.

No one thought seventy-five thousand workers in Pennsylvania would go on strike, but they did. At least 10,000 of those strikers were children. That evening, stopping on the outskirts of Philadelphia, Mother Jones stirred up the sweaty crowd with a speech. She called millionaires “hobos and bums” and scolded lawmakers and factory owners for hiring boys and girls to do grownup work.

That evening, stopping on the outskirts of Philadelphia, Mother Jones stirred up the sweaty crowd with a speech. She called millionaires “hobos and bums” and scolded lawmakers and factory owners for hiring boys and girls to do grownup work. The crusaders reached Jersey City on July 22nd. The next day, they piled into a ferryboat to cross the Hudson, then paraded through the streets of Manhattan waving their banners.

The crusaders reached Jersey City on July 22nd. The next day, they piled into a ferryboat to cross the Hudson, then paraded through the streets of Manhattan waving their banners. The children never got to see the president. Warned about possible arrest and probable disappointment, Mother Jones only took three boys with her all the way to the president’s summer mansion, but Teddy Roosevelt refused to see them. Back in Philadelphia, the strikers were too hungry to hold out any longer. The strike was over.

The children never got to see the president. Warned about possible arrest and probable disappointment, Mother Jones only took three boys with her all the way to the president’s summer mansion, but Teddy Roosevelt refused to see them. Back in Philadelphia, the strikers were too hungry to hold out any longer. The strike was over. In 1971, no one could have imagined that Ireland would have a pro-contraceptive female president (Mary Robinson) by 1990, or that she would be succeeded by another female president in 1997 (Mary McAleese).

In 1971, no one could have imagined that Ireland would have a pro-contraceptive female president (Mary Robinson) by 1990, or that she would be succeeded by another female president in 1997 (Mary McAleese). Back in Dublin, they were met by customs officials and cops. As onlookers gaped, the women waved tubes of contraceptive creams and jellies over their heads and read aloud from an article on birth control they’d clipped from a magazine. Then, for dramatic effect, they scattered what they hoped looked like birth control pills (the aspirin) on the floor. The condoms, however, they kept for themselves.

Back in Dublin, they were met by customs officials and cops. As onlookers gaped, the women waved tubes of contraceptive creams and jellies over their heads and read aloud from an article on birth control they’d clipped from a magazine. Then, for dramatic effect, they scattered what they hoped looked like birth control pills (the aspirin) on the floor. The condoms, however, they kept for themselves. Throughout the next decade, a number of bills concerning birth control were debated and voted on, allowing small concessions here and there. The Health Act, passed in 1985 and amended several times, went a long way toward making contraceptives available in Ireland. Censorship laws were reformed to allow mention of family planning.

Throughout the next decade, a number of bills concerning birth control were debated and voted on, allowing small concessions here and there. The Health Act, passed in 1985 and amended several times, went a long way toward making contraceptives available in Ireland. Censorship laws were reformed to allow mention of family planning. In October, 2012, Savita Halappanavar, a 31-year-old married dentist, began to miscarry due to a bacterial infection. At the University Hospital Galway, she begged for a medical abortion, but, since the fetus still had a heartbeat, she was denied one. According to one report, an assisting doctor, when asked why they couldn’t intervene, said, “You are not dying enough.”

In October, 2012, Savita Halappanavar, a 31-year-old married dentist, began to miscarry due to a bacterial infection. At the University Hospital Galway, she begged for a medical abortion, but, since the fetus still had a heartbeat, she was denied one. According to one report, an assisting doctor, when asked why they couldn’t intervene, said, “You are not dying enough.” Two years later, on October 28, 2014, while candlelight vigils were held across Ireland in Savita’s memory, a small group of pro-choice activists again boarded a train in Dublin and headed to Belfast.

Two years later, on October 28, 2014, while candlelight vigils were held across Ireland in Savita’s memory, a small group of pro-choice activists again boarded a train in Dublin and headed to Belfast. Why are LGBTQ rights, especially those which expand and strengthen the institution of marriage, winning in Ireland (and the U.S.), while women’s reproductive rights are so severely lagging?

Why are LGBTQ rights, especially those which expand and strengthen the institution of marriage, winning in Ireland (and the U.S.), while women’s reproductive rights are so severely lagging? This River of Courage

This River of Courage This happened in McKinney, Texas on Friday, June 5, 2015. Once again, cellphone activism was used to alert the nation. The video went viral. By that Sunday, Officer Eric Casebolt was off the job. Some commentators said he was a “bad apple.” Others said was a good cop having a very bad day. Both miss the point. This is not about a lone officer’s failure to do the “right” thing or even the “helpful” thing. It’s about us.

This happened in McKinney, Texas on Friday, June 5, 2015. Once again, cellphone activism was used to alert the nation. The video went viral. By that Sunday, Officer Eric Casebolt was off the job. Some commentators said he was a “bad apple.” Others said was a good cop having a very bad day. Both miss the point. This is not about a lone officer’s failure to do the “right” thing or even the “helpful” thing. It’s about us.

Puritan fathers, lips stiff as church pews, arrived in the New World with worthy dreams. They would build a shining city on the hill, a New Jerusalem of parks, libraries, and schools, and tend lovingly to the poor and ill.

Puritan fathers, lips stiff as church pews, arrived in the New World with worthy dreams. They would build a shining city on the hill, a New Jerusalem of parks, libraries, and schools, and tend lovingly to the poor and ill. On October 27, the three Quakers walked hand-in-hand to the Hanging Elm, Mary in the middle. They tried to address the crowd, but drummers had been ordered to maintain a steady beat and drown out their voices.

On October 27, the three Quakers walked hand-in-hand to the Hanging Elm, Mary in the middle. They tried to address the crowd, but drummers had been ordered to maintain a steady beat and drown out their voices. Mary Dyer waited out the long winter on Shelter Island, no doubt grieving the friends she’d watched die before her. And then one day in May, she returned to Boston clothed, as it were, in disobedience, once again defying the law of “Quaker banishment.”

Mary Dyer waited out the long winter on Shelter Island, no doubt grieving the friends she’d watched die before her. And then one day in May, she returned to Boston clothed, as it were, in disobedience, once again defying the law of “Quaker banishment.”